I travelled to Sri Lanka in 2000 (from 4/10/2000 to 19/10/2000) on an Emergency Passport which caused me some trouble at the Bandaranaike Airport. I was asked if I was in fact a returning Sri Lankan, a rather unexpected though not entirely unthinkable suggestion considering my South Asian ancestry. I was in Sri Lanka to observe the elections for the USAID Mission to Sri Lanka and I was identified as “an official of the National Democratic Institute”. My connection to NDI was anchored in electoral reform work sparked by the Reformasi movement. A few others and I were tasked with observing election monitoring groups. It was a reasonably light task — and it came with a car and dedicated driver, Tuan Arifeen Aniphon (a Sri Lankan Malay) – and while I wanted to be sent to Jaffna (I was always excited by the prospect of danger) I was in fact sent just north of Colombo to Puttalam, home to many Tamil-speaking Muslim refugees pushed out of the North by the LTTE but not entirely welcomed by the Sri Lankan state either. The stories that swirled around me were of the local political warlord and the politics of vengeance in the area, which added to my sense of the island’s political culture.

Later, reading Micheal Ondaatje’s “Anil’s Ghost”, I began to grasp a little of the terrifying culture of violence that scars the country although I had read KM De Silva’s “Reaping The Whirlwind” on my way back to KL – with its somewhat bloodless documentation of anti-Tamil progroms that preceded the rise of radical groups like the LTTE. In my diary I note: “5 hour lay-over in At Bangkok numbs the brain .. Sit with De Silva’s book and have a hard time trying to figure him out. Comes close to being, in Sunila’s words “too Sinhala” which I read as a position where he notes the privileges of (some) Tamils as if to explain the ‘Sinhala’ response. He comes close but thus far (p.–) has pulled away from a justification of Sinhala-Buddhist ressentiment.”

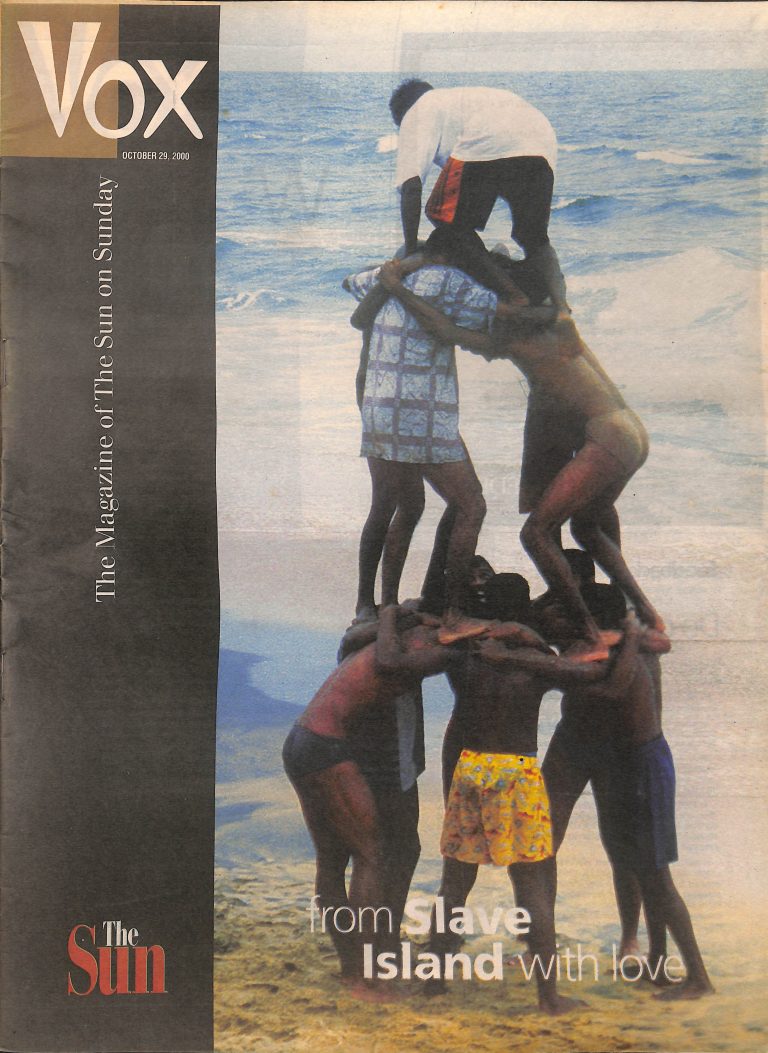

The late Sunila Abeysekera‘s personal story and her penetrating analysis helped with my understanding of a complex society and its history. I wanted to hint at this complexity in my essay “From Slave Island With Love” which was reproduced, I was told, without permission in an English daily, The Island, but also earned me a call from a Malaysian lawyer and LTTE sympathiser. Apparently, the last paragraph of my essay irked him: “The question really is, I’m told, whether they are willing to pay the price of peace. And so between Rohan Edrisinha’s big picture and my Slave Island miniature is a continent of possibilities. For an outsider, in love with the beaches and hills, with a people so full of promise, one can only hope that those of us in the international community support the peace instead of fuelling the war.”

This essay might not have been written because I had problems with my hosts, USAID, who insisted that I could not stay on after the elections and write about the country. They wanted me to leave immediately, arguing that my presence in the country sponsored by them, did not allow me to engage in other activities. I was incensed but took some good advice (I can’t remember from whom) and checked out of the Oberoi quietly and went to a quaint hotel around the corner on Alvis Terrace called Lake Lodge.

My diary provides a fuller account of my first visit to the Republic including interviews academic & playwright Sumathy Sivamohan, playwright & lawyer Visakesa Chandrasekaram and media activist Sharmini Boyle. It also notes some indiscretions but that’s a whole other story.

I have travelled to Sri Lanka several times since but haven’t written much about the country except this comment piece, “Roadblocks To Peace” in the Malay Mail.